When I Don't Recognize What's In Front Of Me

My perception is not more important than your identity.

Every decade or so a meme goes around social media that challenges you to find the book characters who, together, represent you. Like the book nerd I am, I love that meme, and I’ve always known exactly how I’d answer. The first two characters I choose are the ones that I’ve felt guiding me through life since I first met them as a small child: Anne Shirley and Jo March.

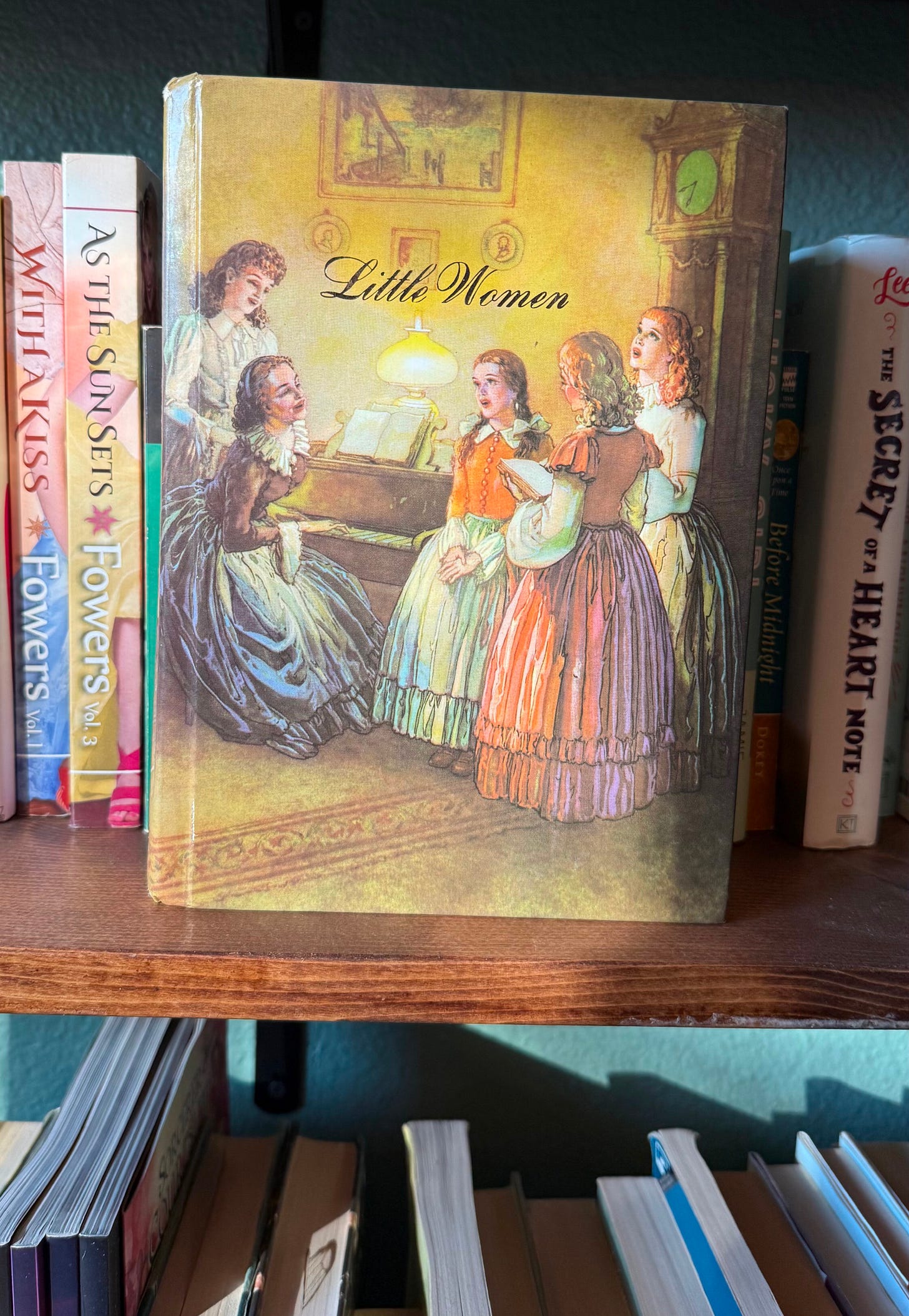

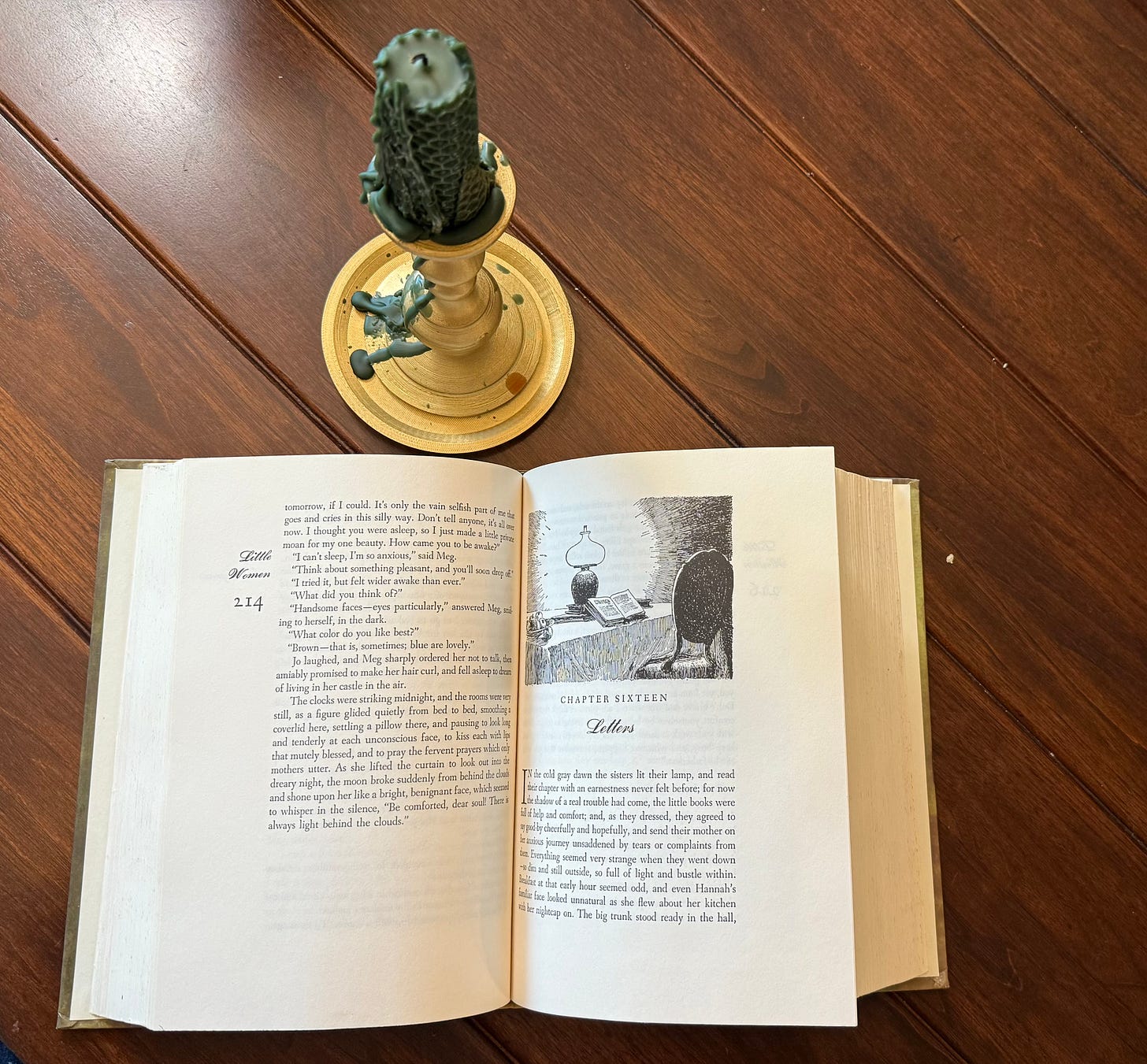

I remember vividly the first time I read Little Women. I was eleven years old, and my mom had finally trusted me enough to let me read the beloved vintage copy her dad had bought for her when she was a kid—gorgeously crafted, with soft linen covers and beautiful interior illustrations. One memory is especially vivid: the day I was reading it in the car, got carsick, and puked, with my mom yelling “DON’T THROW UP ON THE BOOK, CINDY LYNN!!!!” as she drove. (I dodged the book and got my clothes instead, but that had a happy ending, too, since it meant we took a detour to a nearby Target and bought a periwinkle legging set that was my favorite outfit for the whole rest of the year.)

But what I most remember about that reading experience was Jo. Fiery Jo, with her hot temper, her vibrant sense of justice, her big dreams, her big words, her sense that she was meant for more than the restrictions of her patriarchal world. I saw myself in her, a twin soul to my own: writing feverishly, her whole life shaped by her love of stories. I read all of the sequels (though, truthfully, didn’t like them very much because I hated the idea that Jo would give up her writing and disparage it as unimportant simply because she’d gotten married and had kids).

As I grew older, I returned often to the narrative arc in which Jo learns to control and to make peace with her anger. My own anger, especially as a preteen and young teen, felt like a wild, untamable thing, something that drove me more than I drove it. Jo—and her Marmee, confessing “I am angry every day of my life”—gave me a blueprint for how to be a wildfire girl without burning down everything around me. Later, when I became a parent, I returned again to Jo as a teacher—this time, a reminder to have patience with my own wildfire girl.

I first saw the suggestion that Louisa May Alcott was trans—and the implication that, perhaps, her1 lightly veiled self-insert character Jo March might be trans as well—maybe a decade ago. The idea shocked me: everything about Louisa (who more commonly went by “Lou” or similar variations) seemed to me to be tied up in a feminine identity. She rebelled against the trappings of Victorian-era femininity because she did not think women should be bound by them, didn’t she? She had an expansive view of what a woman could be, nurtured by an unconventional family. Her frustration with a society dominated by men felt so real to me, so vibrant, so relatable to a hotheaded girl with big dreams growing up in a conservative religious community in the American South. I loved being a girl, but I didn’t love the models my society was showing me for what a girl was. I knew being a girl could be bigger, wilder, more exciting than that. Just as Lou had.

Hadn’t she?

I encountered the idea of Lou Alcott’s possible transness again two years ago, in the hotly debated op-ed “Did the Mother of Young Adult Literature Identify as a Man?” by trans author Peyton Thomas. And as I read his arguments for Lou’s potential trans identity, I found myself being convinced… and convicted.

It is impossible to ever truly know the gender identity of a writer who lived in a time in which the gender binary was absolute and society had neither room nor language for the trans experience. The words “transsexual” and “transgender” were not coined until the mid-20th-century. As such, nobody will ever really know how Lou Alcott might have identified if they had been transported to 2025. But we do know that they wrote these statements:

“I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man's soul put by some freak of nature into a woman's body.”

“I long to be a man.”

“I was born with a boy’s nature.”

This doesn’t even count the number of ways that Jo in Little Women is also male-coded, referred to often with adjectives like “gentlemanly.”

Lou identified as “a gentleman at large” and “a man of all work;” “papa” or “father” to their nephews; Bronson Alcott called Lou his “only son”.

The 19th century understanding of gender—especially among the Transcendentalist movement in which the Alcott family was active—was very different than the way we understand gender in 2025. But if nothing else, I think it’s extremely clear that if Lou Alcott was alive today, they would almost certainly not identify as a woman.

I’ve written a lot before about my journey to learn to identify plants and their edible and medicinal properties. Several years ago, I embarked on a quest to learn to identify the evergreen trees in my area—a category of plant that I’d previously dismissed as dull, depressing, and all-the-same. For most of my life, I’ve favored the deciduous trees of my home forests in North Carolina, the kind that make lacy woodlands with little underbrush and lots of dappled sunlight. Evergreens felt dark and forbidding to me, and when I looked at one my brain just said “pine tree,” seeing only a cartoon Christmas tree—roughly triangular with pointy needles.

The first tree whose name I learned was the one that I can see through the window from my writing desk. It’s tall, with shaggy branches that droop under the weight of brush-like branchlets coated in short, sharp needles. It’s my neighbor’s tree, but a good number of those curving branches cross the fence and hang into our yard.

I started researching, focusing especially on its eye-catching shape: long, thin primary branches that curve out from the tree and then swoop back up at the end, giving the branches a gentle U-shape. Before long, I found pictures of a locally-common tree that looked like the right shape, with those distinctive swooping branches. Aha! I thought. It’s a cedar! (I even mentioned it by that name in a newsletter at one point.)

I went around for months calling my neighbor’s tree a cedar. (At that point, I didn’t even have enough education to know that the locally common tree I was trying to reference is actually called a western redcedar, and isn’t in the cedar family at all, but is a type of cypress.) And then I learned more, and I realized that the only thing the backyard tree has in common with western redcedars are those drooping branches—everything else, from its pointy needles to its bark to its color, are entirely different. I discovered that evergreens with painfully sharp, short needles are actually spruces. I discovered that there are actually a lot of unrelated evergreen types in Oregon that grow similarly curved branches. And, finally, I managed to positively identify the tree in the backyard as a Norway Spruce.

Since then, I’ve come to love that tree and its branches that lean into my backyard. I’ve learned about the edible and medicinal properties of spruce; I’ve harvested spruce tips every spring for salads, pasta, and syrups that make my coffee or shaved ice taste like a mountain forest2. As I’ve come to recognize its true nature, that Norway Spruce has become a friend.

But here’s the thing. That tree was always itself; it was always a Norway Spruce, never a western redcedar.

The only thing that changed was my understanding.

One of the first executive orders signed by the incoming president on Inauguration Day was an order declaring the existence of only two biological genders. It’s not clear yet what the full extent of the effects of this order will be—or how it might be challenged in court—but it certainly attempts to establish legal precedent for removing the rights of trans and nonbinary people in the US to identify as their true selves. Besides being deeply unscientific, it is also deeply inhumane. I watched trans and nonbinary friends react to this order with shock and grief, worrying that they might lose legal recognition for their passports and driver’s licenses while also grappling with the betrayal of a portion of the electorate gleefully declaring that trans people do not exist.

I know where this thinking comes from. I grew up homeschooling in the Bible Belt in the 1990s, surrounded by a culture of conservative Christian activists. I was raised in a church that considers gender essentialism and “traditional families” divine doctrine. As a teen, I knew that being gay was a grave sin; being trans was the kind of thing we didn’t even whisper about.

But trans and nonbinary people have always existed. Some of the oldest cultures for whom we have stories had understandings of gender that were far more expansive than the modern American binary. Even in times of great social repression, even in the fictional past the right wing clings to in which “traditional families” reigned supreme, trans people existed. Many people throughout history even fully transitioned to living as their chosen gender, their trans identity only realized after their death.

Regardless of whether 15-year-old Cindy, chafing at the confines of what she felt she could accomplish as a girl, understood—trans people exist, and have always existed.

Regardless of what today’s politicians believe—trans people exist, and have always existed.

My ignorance of botany did not make the Norway maple in my backyard into a cedar tree.

And my ignorance of history did not make Lou Alcott a cis woman.

At first, thinking of Lou as trans made me feel a little betrayed. Hadn’t Lou and Jo been fighting for The Sisterhood? Hadn’t they been advocating for girls like me, who felt stuck inside the walls of patriarchal society? Hadn’t they been illustrating the idea that girls can be angry, girls can dream, girls can achieve? Did every historical female who adopted traditionally male-coded dress or language need to be read as trans, rather than a woman using her creativity to outwit the limitations placed on her?

What I’ve come to understand, mulling it over in the last few years, is that it is not a dichotomy. The idea that trans rights come at the expense of women’s rights is patently false. No trans man is out there advocating for women to stay in the kitchen; usually, trans and nonbinary activists are the loudest voices for gender equality. Trans and nonbinary people experience sexism and gender-related violence at far higher rates than cis women.

For as long as we’ve been having conversations about gender roles, trans and nonbinary people have been fighting for the idea that everyone has the right to determine their own destiny—women, men, and everyone who exists outside of the gender binary. It’s far past time for cis women like me to stand up to protect and defend our trans siblings, just as they have protected and defended us.

What I’ve come to understand is: liberation is a group project. It is not women vs men, Sisterhood vs World. It is everyone who has ever been misjudged, everyone who has been told they cannot do something because of the chromosomes they were born with, banding together and lifting one another. Cis women, trans women, trans men, nonbinary and genderqueer people—even the cis men who have been told they are too soft, too weak, too “girly.” It is a rising tide that lifts all boats.

It is Lou, convinced that they have a man’s spirit in a woman’s body; it is Jo, wishing she had been born a boy. It is me.

I hope it is you, too.

Poetry Corner

(I’ve decided a goal for my newsletters this year is to share more poetry! Sometimes it will be my own, like the pantoum below; other times, favorite poems that have moved me recently or feel applicable to the subject matter.)

There is something at the center of me, which burns

when you rake your words across my skin

insisting I am not will not ever be

worthy to inhabit the world you live in:

When you rake your words across my skin,

try to build a cage of scars

worthy to inhabit the world you live in,

The flames run down me from scalp to nails

Try to build a cage of scars

insisting I am not will not ever be—

The flames run down me from scalp to nails.

There is something at the center of me which burns.

Support Trans Authors!

Here are a couple of my favorite trans authors to support! Buying books by trans authors is one way to directly support trans people right now. Trans authors face pushback on multiple fronts: the new administration’s direct attack on trans rights and trans identities, as well as the wave of book bans that has particularly targeted books by and about trans people.

M. K. England: Young adult and middle grade books steeped in delightful nerdery! Latest book: Roll For Love

Alder Van Otterloo: Middle grade books that are a perfect mix of heartfelt and fun, with a generous dash of folk magic. Latest book: The Beautiful Something Else

Anna-Marie McLemore: Young Adult fantasy and magical realism that explore both Latinx and queer identity, written in the most lush, evocative prose you can imagine. Latest book: Self-Made Boys

Kacen Callender: Middle grade, young adult, and adult books woven with magic, lyrical prose, and an exploration of race, gender, and sexuality. Lates book: Infinity Alchemist

A. J. Sass: Middle grade contemporary books that tackle gender and Jewish identity along with friendship and big dreams. Latest book (co-written with Nicole Melleby): Camp Quiltbag

I’m using a variety of pronouns in this essay to refer to Lou; it feels wrong to use solely female pronouns, but also wrong to use solely male pronouns when it’s impossible as a modern reader to know if Lou would have identified as male or nonbinary. I’ve chosen to use female pronouns in this beginning paragraph, and then nonbinary pronouns throughout the rest. It’s probably the wrong choice, but it’s the best one I can come up with. ;)

You may think this sounds gross, but you are wrong. Evergreens have a minty, citrusy, wild taste that’s impossible to describe but utterly delicious. I’ve gotten several skeptical people hooked on what I call my “tree latte.” 😂

I've been on the verge of tears for most of the day and this pushed me over the edge. I appreciate your words so much.

I know we've had this discussion before, but Jo and Anne were also among the first characters with whom I identified (I actually have a copy of that same book, with the beautiful illustrations and everything. My grandmother gave it to me for Christmas when I was a girl.) Like Jo, I often wished I'd been born a boy. Like Jo, I found it incredibly unfair to have been born a girl. I know too many trans individuals to say that I understand what they go through, but I can certainly empathize.

You made me think about what characters I most identify with and the VERY FIRST that came to mind was Murderbot and now I’m wondering if I should worry about that 😆